Friday, June 30, 2006

“Could I get some water to drink?”

I was thirsty. I was interviewing the father of a family in the Atharamura forest in Tripura, a remote hilly region in northeast India, home to the indigenous Reang community who practice slash-and-burn (jhum) cultivation. As a member of TARU, a development research group, I was leading a multi-disciplinary research team, of architects, civil engineers and anthropologists, to investigate (on behalf of the govt. of India) shelter and drinking water conditions, towards preparing a techno-economic action plan for improvement.

I was thirsty. I was interviewing the father of a family in the Atharamura forest in Tripura, a remote hilly region in northeast India, home to the indigenous Reang community who practice slash-and-burn (jhum) cultivation. As a member of TARU, a development research group, I was leading a multi-disciplinary research team, of architects, civil engineers and anthropologists, to investigate (on behalf of the govt. of India) shelter and drinking water conditions, towards preparing a techno-economic action plan for improvement.The family I was interviewing lost three children to gastroenteritis, the last one a 15 year old boy, the first in their family to be going through school, who had suffered a slow, painful death. Gastroenteritis was endemic here, especially in the dry seasons, continually claiming young children, and fundamentally on account of the complete absence of basic infrastructure that should have been provided by the govt, despite the huge amounts allocated for this.

After hearing the account, I recall I asked for some water to drink and drank that. I was thirsty. It never struck me that I was doing anything untoward. In a few hours I was very sick ...

I was scheduled to return to Calcutta the next day – to be present for my son Rituraj’s second birthday - and come back a few days later. In Calcutta, I saw a doctor and took a course of medicines for the shigella-like infection. I thought that was over and done with and returned to Tripura. But meanwhile, one of my team-members in Tripura, Sajish, a young civil engineer from Kerala, fell ill. Perhaps malaria, or typhoid. He had been taken to a district hospital in a remote militancy-affected region of the state, and the conditions there – made to lie on the verandah outside the ward, with dogs ferreting in garbage – had shaken him badly, and he was in a sad state.

Sajish returned to the state capital Agartala, and I remained there to look after him while he was admitted to the govt hospital. He was not in a state to travel home. I planned and assigned the field research work, sent off the team to the interior regions for their village surveys (ably managed by my architect/friend Deva), and kept myself busy in Agartala collecting study-related information and reports, meeting officials, academics, coordinating with the field team etc. And every day, in the morning and in the evening, I would visit Sajish at the hospital, carrying food cooked for him from the guest house I had put up in, talking to the doctors and nurses, getting his tests done, buying his medicines, communicating with his family and so on. He was there for 10-12 days before going back home. There he was diagnosed for typhoid, and fortunately recovered his health. (Six years later we were together on another field research mission, just after the super-cyclone hit Orissa.)

But after Sajish left, I fell ill. I developed a very severe allergic condition, with my skin swollen and red, itching like mad, and scratching only made the skin more inflamed and with a burning sensation. Then the joints of my fingers and arms became painfully stiff. It was hellish. I took some anti-allergic pills. I visited the dermatologist at the hospital, who prescribed some medicines. The work in Tripura was also almost complete, and I returned to Calcutta. At home, I consulted an orthopedist, who too prescribed some medicines and tests. The stiffness spread to all my joints, coming and going, now here, now there, until I was in a permanent condition of extreme pain, the whole body throbbing with pain, and barely able to move at all.

In this condition, I lay in bed, one Tuesday afternoon. I was in severe pain and in despair. Suddenly, I remembered Jesus Christ, and then my mind took a turn that it had never taken before.

I slipped, into the embrace of the Almighty. For a few minutes, but which seemed an infinity, in the midst of everyday life and the world, lying, awake, but my eyes shut tight, fully aware of yet oblivious to all this, I was somewhere else, and my whole being thrilled in delight, I exploded in ultimate joy, and inside me I was singing, a child, "I don't have to worry since my Lord's with me. I don't care for nothing since my Lord's with me. O Lord, O Sweetness ..."

That was on 30th November 1993.

The next evening my wife Rajashi took me to our family physician, Dr Narayanan, who immediately diagnosed my condition as “reactive arthritis” and I was admitted to a nursing home for a few days. And it was only after visiting me there that the doctor realised the pain I was suffering and prescribed the anti-arthritic indomethacine pills and also other strong painkillers. In the nursing home, I could hear from the next cubicle the tortured cries of a small boy who had suffered a horrid accident, being hit and dragged by a car. He had been brought to get his dressing changed.

The medicines screwed up my digestion system, leaving me with a burning stomach and cramps, and great discomfort. If I didn’t take them, the painful stiffness returned.

Then my father had a minor cerebral stroke. He had a stroke a year and half earlier, and was on medication. But it was a degenerating condition. He was admitted to a nursing home for a few days. A week or so after he returned home, I left for Delhi in connection with research studies I was engaged in. I was there for a fortnight.

My return train to Calcutta was delayed. I rang home, and spoke to my father. I told him I’d be reaching around noon the next day. He started telling me something about my application to the telephone department for restoring STD facility. I told him we would talk about it tomorrow. He asked: we’ll talk about it tomorrow? I said, yeah, we'll do that.

Arriving at Howrah station, I had a minor fracas with a railway official who held me up for not having booked in the luggage van all the boxes I was carrying (of census reports and the like). I took a taxi and reached home. It was around mid-day. I got down from the taxi to find a small crowd of friends and neighbours gathered in front of the house. My father had been asleep in his bedroom, and the entrance door was latched from within. He was not responding to the knocks and subsequent banging on the door and shouting by the cleaning lady who had come a couple of hours ago. So I had my brother-in-law break into the ground floor with a shove to the entrance door, and we entered to find my father lying in his bed, dead, cold.

His death was the final and most precious gift that my beloved father gave me.

I love my village

I was a member of TARU's multi-disciplinary team that visited the earthquake affected area soon after. We were undertaking a rapid damage assessment exercise for the govt. of India, towards planning for reconstruction and rehabilitation. The whole area was like a war zone. We went from village to village, surveying the damage, studying the houses, interviewing people from different sections.

We reached a particular village. Or its remains. It was or rather had been a tiny village, and it had been entirely wiped out. What was once a village was now a hillock-like mound of rubble. Each and every person there had perished under stone.

In those ruins we came across a man. He told us he was in the army and had rushed home after hearing about the earthquake in Latur. He reached to find every trace of his home and village wiped out. He remembered various people of the village. There had been one Muslim family. He was calm and collected, and yet somewhat dazed, shell-shocked. He said his home had been the centre of his life. As he went from place to place in the army, he thought of each place in relation to his home. All his purchases were for people at home. His yearly routine centred around his home visits. All his plans, all his feelings were for the people at home. And now this was gone. He said he was trying to come to terms with this, with this vacuum in his life. I was reminded of some lines by John Berger:

"Home is the centre of the world because it is the place where a vertical line crosses with a horizontal one. The vertical line a path leading to the sky and downwards to the underworld. The horizontal line representing the traffic of the world, all the possible roads leading across the Earth to other places. Thus, at home, one is nearest to the gods in the sky and to the dead in the underworld. This nearness promises access to both. And at the same time, one is at the starting point and, hopefully, the returning point of all terrestrial journeys."

(And Our Faces, My Heart, Brief as Photos)

Walking in the rubble of the village, I saw a piece of paper fluttering in the breeze. I went and picked it up. It was a page from a school exercise book. On its two sides, a child had written an essay on “My Village”. The essay began: “In my village we have electricity and piped water. There is a post-office. In my village we have good roads. The village is connected to the state highway by road. Our Gram Panchayat is very active. We have a cooperative society and a store. The society provides good manure and fertilisers and improved seeds. The villagers often come together and work unitedly. ..."

The essay concluded with the sentence: "I love my village very much."

I kept that piece of paper. When our study report was completed, we used the image of the front-side of that page, with the beginning of the essay, on the cover of the report to the govt. of India.

Returning home to Calcutta, exhausted after a gruelling week of field work and a few more days of work at the TARU office in Delhi, and ravaged by all the death and destruction we had witnessed, I hugged my two-year old son Rituraj and wept.

Cuernavaca, Mexico

A friend from Cuernavaca, Mexico, had once written to me :

A friend from Cuernavaca, Mexico, had once written to me :Cuernavaca is a pretty nice city but the main thing is the mountains and the perfect year-round weather. There is only about a 10 degree fluctuation in temperature over the course of the year. It is always cool during the night and pleasant during the day. The low tends to be between 60-70 degrees and the highest 75-85. There are probably not that many places in the world where the climate is so perfect, so I am happy to be living in one of them these last 5 years. There is a dry season and a wet season as well. We are coming to the end of the wet season right now so everything is very, very green. There are always flowers in bloom, butterflys and birdsong and hummingbirds to watch and listen to. From what I hear of Calcutta, it is very hot and there is great poverty. Please tell me about your life there.

About Calcutta

In reply to the enquiry about Calcutta, I wrote:

In reply to the enquiry about Calcutta, I wrote:Calcutta is near the Tropics, very flat, alluvial, estuarine plains, close to the delta (where the river Ganga, which begins in the Himalaya mountains and runs through the north Indian plains, flows into the Bay of Bengal, which separates India from Burma and Thailand). It is quite hot through the year. Between December and February, it is cold and dry, the temperature coming down to 10-12 Celsius. There's a very brief spring, when trees start sprouting, flowers start blooming, fragrance of leaves and flowers starts filling the air, birds singing, before the hot summer begins. It gets hotter and hotter, April and May being particularly oppressive, with the temp near 40 C, and very high humidity. Around mid-April, people get a welcome break from the heat spell for a few days with strong wind and rain storms coming for the north west. Then the extreme heat continues. Nights are a bit more pleasant, with breezes from the south. In mid-June, the Monsoon rains from the southwest hit the city. Heavy rain pours through the day. The temperature comes down. Several days of hot, sunny weather and again heavy rain. This goes on till September-October. Then it gradually becomes cooler and drier, until late-November early December when the 'winter' begins, with heavy mist rising at night from the river, the nights cold, the sun gentle and pleasant during the day, the trees leafless. I guess its this time of the year that people like most - though not the many who are homeless, for whom winter nights are an ordeal, for whom the street is a pleasant home at night in summer. And in the peak of summer, people wait for the first rains, which come heralded by the fragrant scent of the earth and cool, moist breezes, heavy dark clouds, the terrifying roar and clap of thunder and flash of lightening.

As a lifelong Calcutta dweller, the city is like an extension of one's self, of one's own body. One is aware of nature and the seasons. I have become increasingly discerning of nature and seasons in the city, the feel of the air and the quality of light at different times, and the impact all this has on the psyche of the city-dweller.

Different fruits, berries and vegetables accompany each time of year, defining what people eat then, in various forms - cooked, pickles, relishes, raw fruits etc. May-July is the time when the best mangoes come - India's unique gift to the world. The hot summer is the time for a range of plentiful fruits with high liquid content - water melon being an example - which help people to stay cool. The hot summer is also the time of the piercing, maddening calls of the cuckoo (also called the brain fever bird I think!).

There's a unique marriage between climate/nature and people in any place! It is said that the climate here in Calcutta makes people lethargic, indolent, not industrious and ambitious, content with little. Nature is also bountiful, with fertile soil and rain, many vegetables and fruits growing through the year, fish in the riverine and pond-filled land. The society is stratified, with the common people bound to the soil and its management and to labour, while the propertied are inclined to leisure and non-manual pursuits, including refined arts. The British East India Company arrived in Calcutta in 1690. In 1772 the city became the capital of British India and remained India's leading city until 1912, when the capital shifted to Delhi. The seat of the British Empire in India, Calcutta was a very important city, economically, commercially, politically. But in the last four decades, the once proud city has been brought to its knees and made bereft. There is great poverty and squalour, unemployment, great exploitation and apathy, but also considerable wealth among a small privileged section. The middle class is squeezed and oppressed from all sides, and its backbone and fibre is largely crushed. The state is ruled with an iron fist by a communist party, which is bankrupt and corrupt in every way, and has been successful in pitting classes against each otherwhile feeding off everyone. There is no political opposition in the horizon.

Recently, a real estate and shopping mall boom has begun, giving some satisfaction to the affluent, amidst a scenario of blight and all-round degradation and hopelessness. Lawlessness, hostility, and getting the best for oneself, in whichever way, preferably foul - defines life in the streets of Calcutta. But cost of living is low, and Calcutta is still an essentially human and intimate city, at a human scale, rather than an impersonal one. The people are friendly and gracious, and the visual landscape is also very handsome in many places.

For a trip to Calcutta down memory lane, go here.

Photo: Achinto

Belfast, Sao Paulo, Johannesburg & Calcutta

"How has thirty years of political turmoil affected the European city of Belfast? How has the legacy of apartheid resulted in the polarisation of the African city of Johannesburg? How will the Indian city of Calcutta deal with a population where over 50% of people live in poverty-ridden slums? And how has sudden deindustrialisation defined society in the South American city of São Paulo?

Local architects and urban thinkers discuss these questions, and more, in their personal perspectives on the past, present and future challenges of these cities."

They answer 4 questions:

What is the heritage of your city and how has that played a role in defining your city today?

What are the biggest immediate challenges facing your city?

What is your city’s approach to solving these challenges?

How do you see your city evolving over the coming 5 –10 years?

Read the answers here.

Thursday, June 29, 2006

What do I write?

What do I write, where do I begin… an ocean of rich awareness. One thought, one memory, one tale leads to another, and another, and very soon it’s an unstoppable gush of consciousness, feeling, sensation, meaning, significance and grace, which is beyond the capacity of words or speech to convey, a very frustrating condition no doubt, but to retain one’s calm in the face of this flood of awareness one must dwell in silence, in the void beyond thought and memory, pregnant with pure awareness.

What do I write, where do I begin… an ocean of rich awareness. One thought, one memory, one tale leads to another, and another, and very soon it’s an unstoppable gush of consciousness, feeling, sensation, meaning, significance and grace, which is beyond the capacity of words or speech to convey, a very frustrating condition no doubt, but to retain one’s calm in the face of this flood of awareness one must dwell in silence, in the void beyond thought and memory, pregnant with pure awareness.But the blue-throat must sing.

Here's something I wrote in 1997, when I dwelt in poesia.

Log

Seeing

Beyond the maze of archaeological and scientific mystery:

Unifying mythology and microbiology.

Reading invisible maps and signposts of endeavours, journeys and migrations -

Lonely, unrelenting,

Through medium, geography and temperament,

Culture and climate -

Of the timeless spirit of quest, reunion, and well-being.

Hearing

The silent semaphore calls and responding notes

Of twilight communication,

Between sect and school, through history and thought.

The gentle songs of children’s sweet-throated homage to heroes departed.

Witness

Battlegrounds of the spirit heaped with the corpses of still-born faith

Piled upon humanity’s heritage of ignorance, forgetting and betrayal.

Understanding prophecies and discerning their fulfilment.

Beholding congresses and outpourings of joint celebration and mutual resolve

In amphitheatres of time, space and consciousness.

Visiting temples:

Museums of creation,

Schools

For the journey to the sacred and the divine.

Observing rituals, exemplars of absolution.

Intuiting astounding designs of trans-historical projects

To cultivate the garden of earth.

Voice

Speech, like thread through a garland of buds

Laid in prayer to the nameless one.

Song

Melody,

Revering the train of silent saints,

Heartening the children:

“Don’t forget little ones, don’t forget to walk with me,

Millennia’s suffering did I turn, for you only.”

(Painting: Voyage Beyond Time, by Marianna Rydvald)

Starlight, like remembrance

I dwelt in a rich wash of profound reflection. On the reverse of my boarding pass I wrote:

Starlight, like remembrance, weaving constellations of tales

Floating in immensity.

The human experience, a great Milky Way.

Life and the universe, mind and material,

One mirroring the other,

In infinite rounds of resonance.

Beyond the Prison of Mirrors

In April 1997, I went to Hyderabad, again to contribute towards the research study on urban poverty, which was now being initiated there. I took an afternoon flight to Hyderabad. The flight route was over the Bay of Bengal coast, which was one’s companion below for half the journey, the white line of the waves spilling out on the sand cutting across the window glass. Then the plane swings inland, westwards, and the eastern ghats come into sight. The coastline is still visible, though going further and further away from sight and becoming fainter, but nonetheless still discernable. Finally it reaches the edge of the horizon. Looking directly below one sees the high hills of the western edge of the ghats, well inland. I could see the highest point of the eastern ghats, and also the coastline, a sight one could not get even if one stood at the top of the highest peak below, for the sea was too far away. Wow! Was I thrilled! (Last year, on a morning flight from Calcutta to Delhi, in peak summer, in the distance, at the the northern horizon, the majestic Himalayas were one’s companion for a good part of the flight.)

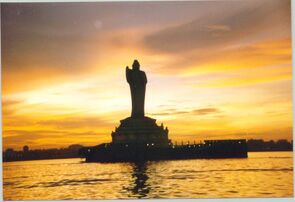

In April 1997, I went to Hyderabad, again to contribute towards the research study on urban poverty, which was now being initiated there. I took an afternoon flight to Hyderabad. The flight route was over the Bay of Bengal coast, which was one’s companion below for half the journey, the white line of the waves spilling out on the sand cutting across the window glass. Then the plane swings inland, westwards, and the eastern ghats come into sight. The coastline is still visible, though going further and further away from sight and becoming fainter, but nonetheless still discernable. Finally it reaches the edge of the horizon. Looking directly below one sees the high hills of the western edge of the ghats, well inland. I could see the highest point of the eastern ghats, and also the coastline, a sight one could not get even if one stood at the top of the highest peak below, for the sea was too far away. Wow! Was I thrilled! (Last year, on a morning flight from Calcutta to Delhi, in peak summer, in the distance, at the the northern horizon, the majestic Himalayas were one’s companion for a good part of the flight.)Arriving at Hyderabad, I looked at the city below and very soon I could see the large Hussainsagar lake and my eyes searched to spot the Buddha statue in the middle of the lake, installed 5 years earlier (after having sunk to the bottom of the lake accidentally when it was taken for installation in 1988; while doing a short course on remote-sensing at the National Remote Sensing Agency in Hyderabad two years earlier, I had seen a satellite image of the formerly-sunken statue). I saw it, a white needle over the dark water! My eyes stayed with the statue as the plane descended, until a fraction of a second before touchdown, when its top flashed briefly over the city before going out of view.

I was really taken by that sight, of the gigantic Buddha statue over the lake bearing the name of the grandson of Prophet Mohammed, and spoke of this to friends during the trip. Returning to Calcutta after the visit to Hyderabad, I had with me a copy of the Dhammapada which I had found at the airport bookshop and begun reading avidly in the lounge. It was late evening when the plane reached Calcutta. I remembered my sight from the plane over Delhi six months earlier, and the reflection on stars and Mahatma Gandhi. I remembered the Great Calcutta Killing, of 16 August 1946, and wondered how my city below looked, on that night of arson.

On the taxi ride back home, I hurriedly scribbled some notes on the reverse of my boarding pass, to put down the rush of thoughts and reflections that came to mind.

But between the ascent over Delhi and the descent in Calcutta – much had happened, and all entirely unanticipated, turning me upside down, transforming my life. A veil had been pierced … the prison of mirrors had been shattered. India, freedom, independence, partition, Hindu-Muslim riots etc etc – I had become one with all this, this was now the stuff of my own life.

I rewrote what I had earlier written, adding a final line, and a title:

The Prison of Mirrors

Starlight, like remembrance, weaving constellations of tales

Floating in immensity.

The human experience, a great Milky Way.

Life and the universe, mind and material,

One mirroring the other,

In infinite rounds of resonance,

Awaiting the shattering of mere echo and image.

And I began another word-log, bringing together Delhi, Calcutta and Hyderabad. But that was only completed some months later, after I had visited Hyderabad a few more times in connection with the poverty study. And this was now a city that was dearly beloved to me. In August 1997, I attended and participated in the “Festival of the Subcontinent” in Hyderabad, organised by COVA, to commemorate the 50th anniversary of independence of Pakistan, India and Bangladesh. Of course, I saw the Hussainsagar lake and the Buddha statue several times every day, as well as the waterfront adorned with statues of Andhra Pradesh’s luminaries from various fields.

As I write this, my colleague Prodyut tells me that his cellphone was pick-pocketed a couple of days ago. I remembered being pick-pocketed during the Hyderabad Festival, Prodyut had also been there. But that did not mar my spirits, for I was truly flying high during that week in Hyderabad, I was not in this world, but in some other heaven. What a rich experience it was! I bought and heard some fantastic music albums. I even came across an important book on the Buddha in a pavement book-sale while walking along casually; reading that in turn triggered another rich wash of realisation. (My friend Achinto, the documentary photographer, was also there, and during a visit to the magnificent Golcunda fort, he photographed me as I stood over one of the high ramparts of the fort and told a tale to some school boys who were there, gesticulating with my hands and throwing my arms out over the outstretched landscape. He later said he wanted to capture me in this inspired-possessed state!)

I wrote:

Beyond the Mirror

Night.

Ascent.

Lights of the city.

Memories :

of funereal processions,

of once beloved saints,

and conflagrations, of riotous arson,

spreading hatred’s poison fire.

The stars, far away,

faint dots in the black sky.

Day.

Descent.

The needle of eternal knowledge,

poised on the still waters of the ocean of sacrifice

ringed by the pearls of devotion and service.

The light of the city dispells the noon of despair,

streets paved with jewels of wisdom,

beckoning the children,

to come,

and build tomorrow’s citadel of peace.

On 16 August 1997, Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan passed away. Since I first heard his songs a couple of years earlier, I had been set on fire as it were by his voice, which sent me into a fevered inner quest. At Hyderabad, on the evening of 17 August 1997, the Pakistani singer Reshma performed at the Festival. Before the programme began, the organisers were playing some awesome songs of Nusrat, from private studio recordings. The large gathering of people stood in silence for two minutes in homage to the great master as the programme began. As Reshma sang, and I remembered Nusrat, I looked up at the star-lit sky. There was a big full moon smiling down. For me, that was the great water-melon of voice of the music of mystical Islam.

Returning to Calcutta, I completed my account of the Delhi-Calcutta-Hyderabad experience.

Beyond the Prison of Mirrors

Night.

Ascent.

Lights of the city.

Memories:

of funereal processions

of once beloved saints,

and conflagrations, of riotous arson,

spreading hatred's poison fire.

The stars, far away,

faint dots in the black sky.

Day.

Descent.

The needle of eternal knowledge

poised on the still waters of the ocean of sacrifice,

ringed by the pearls of devotion and service.

The light of the city dispells the noon of despair.

Streets, paved with jewels of wisdom,

beckoning the children,

to come,

and build tomorrow's citadel of peace.

From great killings partitioning the soul

to joint celebrations for union of hearts:

now is the city truly lit.

The light of the city

glows

with an infinitude of starlight...

a symphony of illumination.

(Calligraphy: The name of the Prophet Muhammad, in mirror images, by Subail Anwar, Istanbul.)

The Buddha's exclamation on enlightenment

I did manage to find the Pali verses eventually (Ch 11, ver 153-54). I also got from Prof Lal a postcard he had printed with this exclamation, in Devanagari, so I was able to get the pronunciation right. Last year, I managed to learn this and set it to melody, to add to my small collection of devotional songs and chants from different faiths and in different langauges. (Rishiraj/Chotu was most amused by my efforts to memorise this while travelling in a Maruti 800 car.)

Anekajatisamsaram sandhavissam anibbisam

gahakarakam gavesanto dukkha jati punappunam.

Gahakaraka! Ditthosi, puna geham na kahasi

sabba te phasuka bhagga gahakutam visankhatam

visankharagatam cittam tanhanam khayamajjhaga.

Which means:

I, who have been seeking the builder of this house, failing to attain Enlightenment which would enable me to find him, have wandered through innumerable births in samsara. To be born again and again is, indeed, dukkha!

Oh house-builder! You are seen, you shall build no house again. All your rafters are broken, your roof-tree is destroyed. My mind has reached the unconditioned; the end of craving has been attained.

|

A few weeks ago I attended the screening of Tathagata, a feature film on the Buddha’s search for enlightenment, made by the Bengali writer and documentary film-maker Shahzad Firdaus. A commendable effort indeed. I was particularly delighted with the language, pure Sanskritised Hindi, which one rarely hears and I myself rarely use now, since I speak a more Urdu-ised Hindusthani in order to be able to communicate with the Urdu-speaking people I mostly have truck with. Not only did I follow every words of the dialogue, it was also deeply satisfying and pleasurable to hear such refined language.

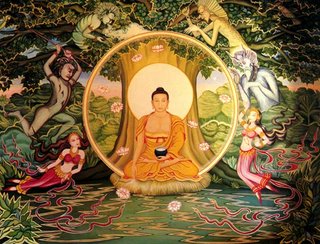

On the internet, I discovered a painting of the Buddha’s enlightenment, by Marianna Rydvald a Swedish painter living in Maui, Hawaii. I am reproducing that below. This image is the wallpaper on my computer screen! For those familiar with the texts about the life of the Buddha, this is a grand scene indeed, of the Buddha prevailing over Mara.

Shantideva

In her sitting room, I looked through a book of photographs, and there was a page with a caption quoting a couple of verses by Shantideva.

Shantideva! I presumed these stanzas were from the Bodhicharyavatara. This text (whose title in English is "Engaging in Bodhisattva Deeds" or "A Guide to the Bodhisattva Way of Life"), is a very important one in Mahayana Buddhism, it is about the heart and vision of a Buddhist monk. Shantideva was a Buddhist monk from southeastern Bengal, who lived in the 6th century AD. After a great urge to read this text, I finally managed to get a Sanskrit-to-Hindi translation from the Mahabodhi temple at Sarnath in 1997, and later a Sanskrit-to-English translation from the Mahabodhi book shop in College Square in Calcutta. (How many books I’ve bought from here, how many serendipitious finds!)

Seeing the lines at Banashree’s mother's - took me back to this text again. So returning to Calcutta, I found the original stanzas in Sanskrit (Ch 8, ver 95-96), and learnt them and set them to melody.

Yada mama pareshama cha

Tulyameva sukham priyam

Tadatmana ko vishesho

Yena traiva sukhodhyam

Yada mama pareshama cha

Bhayam dukkham cha na priyam

Tadatmana ko vishesho

Yattam rakshami netaram

Meaning:

"When both myself and others

Are similar in that we love happiness,

What is so special about me?

Why do I strive for my happiness alone?

And when both myself and others

Dislike fear and suffering,

What is so special about me?

Why do I look to protect myself and not others?"

This encapsulates the enlightenment wish, living for others, the great compassion.

Buddha Purnima in Salzburg

I was in Salzburg, Austria in mid-May, to speak at an international congress on city planning. My presentation was on slums in Calcutta. There were also speakers from East London (South Africa), Alleppo (Syria), Sao Paulo (Brazil) and Istanbul (Turkey). The presentations were very educative. My presentation was well received; though I was speaking about a depressing subject, that of chronic poverty and the failure of public policy, for the conference participants I seemed to personify hope!

I was also able to share some of my sacred text based songs at Salzburg. Buddha Purnima, the full-moon commemorating Buddha's enlightenment (Taurus full moon) this year fell on Saturday, 13 May, while I was in Salzburg. On Buddha Purnima night, I sang the Buddha's enlightenment exclamation, to the heavens, from the balcony of the palace in Salzburg where our conference was held. Perhaps in response, the full moon emerged from behind clouds and lit up the sky! I also sang the verses by Shantideva and my most recent composition, in Hebrew, from the Book of Psalms, "And he shall be like a tree". My friend from RIMC, Abir Samuel had helped me in learning this. There were some Jewish and Israeli participants, and they confirmed that I had got it right.

Back home after the conference, I received an email from Sonja Prodanovic, a participant from Belgrade, Serbia. She wrote:

"Our daily ongoing politics of disintegration is still shocking to us, even paralyzing personally when one returns back home. We have a new split of our State (Montenegro). Not that we mind, but the daily events are burdened with it all, even after 18 years of our self-induced destruction. The war crimes are fading away and war criminals and the dirty money are becoming development initiators. It is only when one gets out from what is for the majority of the people a totally closed State that one realizes what are the real problems of the World. It was an immense gain to us at the SCUPAD meeting to be able to hear all the case studies of really complex, troublesome cities and communities. Add to that the admiration for your personal work, your dedication and the richness of your soul, and the gift you gave us on the balcony under the moonlight, showing I think to all of us present, the possibility despite the reality of Calcutta life, to find the energy as well for such rich cultural elaboration of personal calmness and purposefulness. When in despair I close my eyes and recall your singing and recitals, remembering the strength of the wisdoms, I say to myself that I should be ashamed of thinking that our troubles are great ones. I have learned at a very late stage of my life what a troublesome world we live in, but equally what wonderful people, yet undiscovered, are around. Thank you for the new discovered experience and enlightenment."

I wrote about this to my friend James Aboud, in Port of Spain, Trinidad (we had been hostel-mates and close buddies in London in 1982-83). He replied: "Singing from the balcony under a moonlit sky in Salzburg. It is the kind of scene that makes me want to plan a murder or start a religion!!" He added: "Did I tell you that I am now a Judge of the High Court? I have the robes, but no wig (sadly, as I need one for my baldness!!). It is very relevant and meaningful work, to be a dispenser of justice. Of course, taking an emergency pee at the side of the road is no longer appropriate behavior."

I wonder whether there are many judges in the world who possess James' erudition, taste and sensibility. He is also a first-rate poet. His second volume of poems Lagahoo Poems was published last year.

Gandhi picture

In Salzburg, I also presented a picture of Mahatma Gandhi to the Salzburg Seminar (an American institute, with which I have been associated since 1992). The picture is of Gandhi crossing a bamboo foot-bridge over a creek in Noakahali (now in Bangladesh), where he spent 4 months in late 1946-early 1947, trying to bring peace to the communal violence afflicted district. This picture will be put up at the magnificent library of Salzburg Seminar.

In Salzburg, I also presented a picture of Mahatma Gandhi to the Salzburg Seminar (an American institute, with which I have been associated since 1992). The picture is of Gandhi crossing a bamboo foot-bridge over a creek in Noakahali (now in Bangladesh), where he spent 4 months in late 1946-early 1947, trying to bring peace to the communal violence afflicted district. This picture will be put up at the magnificent library of Salzburg Seminar.In an article some years ago, Andrew Whitehead, who made a BBC Radio series on the partition of India, wrote: "Gandhi visited dozens of villages in his four months in the area. ... his calming presence and message, the concern he showed for both communities, and the sight of India's foremost leader, barefoot, negotiating the narrow bamboo bridges, had an immense impact."

Just a couple of years ago, I learnt from an elderly uncle of mine in London that he had been in the group of peace workers who had accompanied Gandhi to Noakhali. Some of them also stayed back to work and live there.

I thought about an appropriate quote from Gandhi to accompany this pic. That was quite difficult! But I did find one: "Peace between countries must rest on the solid foundation of love between individuals". I think that is marvellously fitting, for the Salzburg Seminar! (It is also virtually identical to the counsel of the Buddha to his friend and disciple, King Prasenjit, on the conduct of foreign policy.)

May peace and love prevail on earth!

Dandi March

Last year I had obtained a print of the photo of Mahatma Gandhi picking up salt at Dandi. This was presented to my alma mater, the Rashtriya Indian Military College, Dehradun, to commemorate the 75th anniversary of the Dandi March. The great Salt March is an event that shook the British Empire.

Last year I had obtained a print of the photo of Mahatma Gandhi picking up salt at Dandi. This was presented to my alma mater, the Rashtriya Indian Military College, Dehradun, to commemorate the 75th anniversary of the Dandi March. The great Salt March is an event that shook the British Empire.Gandhi's articles, notes, letters and speeches from the period of the Dandi March (12 March - 6 April 1930) are to be found in Vols. 48 and 49 of The Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi.

Hey you!

Hey you, out there in the cold

Getting lonely, getting old

Can you feel me?

Hey you, standing in the aisles

With itchy feet and fading smiles

Can you feel me?

Hey you, don't help them to bury the light

Don't give in without a fight.

Hey you, out there on your own

Sitting naked by the phone

Would you touch me?

Hey you, with your ear against the wall

Waiting for someone to call out

Would you touch me?

Hey you, would you help me to carry the stone?

Open your heart, I'm coming home.

Hey you, standing in the road

Always doing what you're told,

Can you help me?

Hey you, out there beyond the wall,

Breaking bottles in the hall,

Can you help me?

Hey you, don't tell me there's no hope at all

Together we stand, divided we fall.

Wednesday, June 28, 2006

Rituraj & Rishiraj

A fortnight ago, I was at the Rishi Valley School, near Madanapalle, in Andhra Pradesh. My wife Rajashi and I had gone to admit our younger son, Rishiraj (11), there. Elder son, Rituraj (15), has been studying there since 2003. He was also returning to school after the summer vacation.

A fortnight ago, I was at the Rishi Valley School, near Madanapalle, in Andhra Pradesh. My wife Rajashi and I had gone to admit our younger son, Rishiraj (11), there. Elder son, Rituraj (15), has been studying there since 2003. He was also returning to school after the summer vacation.After 15 years, our house is now without children. After Rituraj joined RV, Rajashi and I had become even more emotionally attached to Rishiraj (aka Chotu). We are like ghosts or zombies floating through our lives, shell-shocked, distraught!

Sending one's children away - to live with that one becomes hard-hearted. The moment the thought or remembrance arises, triggered by anything, one kills it, for to let it enter the system and bring on the grief is unendurable. One steels oneself aginst this, and tries instead to think of all the good that this school is doing for the children, what a beautiful place it is.

Rishi Valley School

Rishi Valley School was started in 1931, by the thinker-teacher J Krishnamurti, to give expression to his vision of what education must be, what a school must be like, in order to facilitate the blooming of each child according to his / her true self, free of all kinds of false conditioning.

Rishi Valley School was started in 1931, by the thinker-teacher J Krishnamurti, to give expression to his vision of what education must be, what a school must be like, in order to facilitate the blooming of each child according to his / her true self, free of all kinds of false conditioning.In 2003, I got from the school office the booklet on the first 40 years of the school, written based on a research-documentation project. On the bus ride back from dropping Rituraj, while Rajashi was deep in silent sadness, I read the account. I was rivetted and spell-bound by the tale of this institution founded on idealism, the struggle to set it up, the challenges and difficulties, the dark days, the swings between extreme freedom and strict discipline, the exceptional individuals and their characteristic genius, and limitations. I could see the whole thing happening in front of me, as if I was witnessing the events and situations.

The story of the quest for true education, is the stuff of an epic. Those familiar with AS Neil's "Summerhill" would know! Later I sent the booklet to my dear friend Col Arun Mamgain, who was then the Commandant of the Rashtriya Indian Military College (RIMC), in Dehradun. He too was gripped and inspired by the account.

The publication is accessible here.

RIMC

In the context of my challenging work on a slum improvement project in Calcutta in 1997, the year of the 75th anniversay of RIMC, and also the 50th anniversary of India's independence, I awakened to the soldierly qualities and capabilities I had imbibed from the school. During 1998-2003, I visted RIMC regularly every few months, on teaching visits. I developed a close association and attachment with the cadets, being with them through their daily routine, in classroom, sports field, music room, dormitory etc, and tried to motivate them to conscience, excellence and leadership, being a confidante, counsellor. All this was of course made possible by Col Mamgain, who gave me the freedom to do what I felt impelled to do. The school library is also a fabulous resource. Each visit of mine is also associated with the books I found and read, perhaps impossible to find anywhere today. Its not possible to describe what my visits to RIMC meant to me, and how precious and gem-like each of those days was! And of course the beautiful verdant, wooded campus, full of fragrances and bird-song.

Col Mamgain's friendship was also a gift, how I treasure the memory of our long, long conversation-walks, talking mostly about the school, the problems, the possibilities, as well as mutual sharing, through moments of inspiration as well as dejection. My wife and/or son/s had also accompanied me on some of my trips. My friend Achinto, photographer, accompanied me on a couple of visits. I was keen that my sons join the school, but that was not to be.

Owing to my awakening to the demands of the responsibility of managing the manufacturing enterprise (started by my father in 1967) which I had taken up on behalf of my family, I was unable to continue my RIMC visits. There was also the emotional toll. Col Mamgain retired in Oct 04, and the batch of students with whom I had become particularly close graduated.

Anyway, after an assignment in Dubai, Arun Mamgain is now back in Dehradun, where he has settled after retirement. The RIMC Commandant now is Col Prem Prakash, whom I also know well, he was my junior in school, and was the admin officer of RIMC during my early visits. I think I have also become more resilient aginst emotional toll of rich past! So I look forward to being back at RIMC soon.

An essay on the cow

The book has an essay on the cow, written by a small boy. I reproduce that below for everyone's edification. The author writes:

"Why do so many writers prefer pudder to simplicity? It seems to be a morbid condition contracted in early manhood. Children show no signs of it. Here, for example, is the response of a child of ten to an invitation to write an essay on a bird and a beast. … The writer had something to say and said it as clearly as he could and so has unconsciously achieved style.”

The Essay

The bird that I am going to write about is the Owl. The Owl cannot see at all by day and at night is as blind as a bat.

I do not know much about the Owl, so I will go on to the beast which I am going to choose. It is the Cow. The Cow is a mammal. It has six sides – right, left, an upper and below. At the back it has a tail on which hangs a brush. With this it sends the flies away so that they do not fall into the milk. The head is for the purpose of growing horns and so that the mouth can be somewhere. The horns are to butt with, and the mouth is to moo with. Under the cow hangs the milk. It is arranged for milking. When people milk, the milk comes and there is never an end to the supply. How the cow does it I have not yet realised, but it makes more and more. The cow has a fine sense of smell; one can smell it far away. This is the reason for the fresh air in the country.

The man cow is called an ox. It is not a mammal. The cow does not eat much, but what it eats it eats twice, so that it gets enough. When it is hungry it moos, and when it says nothing it is because its inside is all full up with grass.

Tuesday, June 27, 2006

First post

Yesterday I visited the blog of Ahmad Saidullah, from Hamilton, Canada, after receiving his invitation. Being a lover of literature, that was a most delightful experience.

Yesterday I visited the blog of Ahmad Saidullah, from Hamilton, Canada, after receiving his invitation. Being a lover of literature, that was a most delightful experience.As I was responding to him by e-mail, telling him something about myself and my work, and providing URL links to some of my articles and related information, it struck me that blogging was just like this.

We learn from and are formed by the internet, we contribute to the internet, we engage in relationships through the internet... Virtuality and reality enmesh.

Since early 2005, I have had a wonderful friendship with Dr Mrinal Bose, a physician and writer who lives in Sodepur (a suburb north of Calcutta). We became acquainted through the internet. We did meet as well, thrice so far. And thanks to him, since late last year I have been reading and translating the short stories of the Bengali writer Subimal Misra. (A couple of the translated stories were published in Hackwriters.com recently, and one of the readers, Mr IK Shukla, from USA, sent the link to Ahmad Saidullah and then forwarded his comment to me. Ahmad has been extremely generous in reading through my stories and giving detailed suggestions for corrections.) In April, Mrinal sent me the manuscript of his first novel, which he completed in 2001. I have been editing that.

We exchange e-mails regularly, mostly serious and reflective, with our dialogue touching on diverse subjects concerning us. This morning I received a mail from him, where he wrote about Haruki Murakami. In my reply to him I copied a poem I had written some years ago. Once again it struck me that I could be doing such things on a blog.

Yesterday I also heard from my friend Lou Gelehrter, who lives and works in Jerusalem and Bucharest. He sent me his blog link. With everybody blogging, it was time for me to start!

So I googled "how to do a blog site", and soon after, this first post. So here goes!

Photo: Jean Cassagne

Hindu-Muslim ill-will

In 2004, I had applied for a fellowship to take up a project on building positive peace between Hindus and Muslims in India.

In 2004, I had applied for a fellowship to take up a project on building positive peace between Hindus and Muslims in India. "Conflict between Hindus and Muslims has vexed south Asia for over 6 decades. In many parts of urban India, there is near complete spatial, social and cognitive segregation of the two communities. Even in areas that have been largely free of communal violence, anti-Muslim feelings are strong, and there is a lack of any substantive inter-relationship for the majority of urban, educated Hindus. But for centuries, Hindus and Muslims have lived together peacefully, and common folk have together built an ongoing “dialogue of life”. Fundamentalist ideologies are, however, destroying this heritage. Yet Hindu-Muslim conflict is a non-issue as far as the govt. and institutions are concerned, and in mainstream discourse. This silence in turn only works to perpetuate the problem. The future of India, as a secular, democratic, pluralist republic is at stake."

I was unsuccessful in my application! However, a few weeks ago, The Telegraph (Calcutta) carried a 3-part article by Tapan Raychaudhuri, former professor of modern Indian history at the University of Oxford, on Hindu-Muslim ill-will in India. I was very glad to see this subject being written about now.

Tapan Raychaudhuri's article is accessible at:

Part 1, Part 2, Part 3

Responses to his article are here. The author's rejoinder is here.

Maoist revolutionaries

About a month back, I met Rahul Banerji, a social activist from Madhya Pradesh, who was visting his mother in Calcutta. Rahul and I were in school together in Calcutta (1968-72). We met out of the blue in 1988 and have been in touch off-and-on since then. For over 20 years now, Rahul has been working for the rights of the advisasis or indigenous people of central India, and especially against the depredations of corrupt forest officials, contractors, police and politicians. For his efforts he has been thrown in jail several times - on various trumped up charges, including treason. So we had a long dialogue, on various matters. Most interesting for me was our discussion on "Naxalism", in the course of which Rahul made the distinction between "Naxalism" and "Jihadism", two forms of violent political struggle. (A fortnight earlier, at a conference on city planning in Salzburg, Austria, Prof Franz Oswald, from Zurich, phrased something I said as "violence as a planning tool". So this was very much on my mind.).

About a month back, I met Rahul Banerji, a social activist from Madhya Pradesh, who was visting his mother in Calcutta. Rahul and I were in school together in Calcutta (1968-72). We met out of the blue in 1988 and have been in touch off-and-on since then. For over 20 years now, Rahul has been working for the rights of the advisasis or indigenous people of central India, and especially against the depredations of corrupt forest officials, contractors, police and politicians. For his efforts he has been thrown in jail several times - on various trumped up charges, including treason. So we had a long dialogue, on various matters. Most interesting for me was our discussion on "Naxalism", in the course of which Rahul made the distinction between "Naxalism" and "Jihadism", two forms of violent political struggle. (A fortnight earlier, at a conference on city planning in Salzburg, Austria, Prof Franz Oswald, from Zurich, phrased something I said as "violence as a planning tool". So this was very much on my mind.).In the last week of May, historian Ramachandra Guha, together with 5 others, comprising the ‘Independent Citizens’ Initiative’, travelled through the Maoist controlled areas of central India. The hilly and wooded terrain here is now home to a brutal civil war played out away from the national gaze and mostly unreported by the national press. It is, however, a conflict of the gravest importance to the future of India. According to the ministry of home affairs, the Communist Party of India (Maoist) is active in more than one hundred districts of the country, and at least fifty-five are reckoned to be ‘seriously affected’ by revolutionary violence. Two months ago, the prime minister of India said that this constitutes the gravest internal security threat to the nation, surpassing in its gravity the insurgencies in the North-east and in Kashmir.

The Telegraph carried a 4-part article by Guha, on Naxalites, or the Maoist revolutionaries in India.

Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4

The cuckoo

The name of this blog - is inspired by the 19th century tale of the prince who became a cuckoo, one of Tibet’s most cherished tales, illustrative of Buddhist teachings.

The name of this blog - is inspired by the 19th century tale of the prince who became a cuckoo, one of Tibet’s most cherished tales, illustrative of Buddhist teachings.I discovered this book in Modern Books in Dover Lane, in Calcutta, run by the Tiwari brothers. (Over more than 15 years, I have bought so many books from this shop, and how much I've been enriched and enabled by those books. But the Tiwaris are humble, barely educated. In my consciousness, the soil of the region they are from, eastern U.P., is a sacred mother.) The Prince who became a Cuckoo: A Tale of Liberation, by Lo-Dro, translated by Geshe Wangyal, Theatre Arts Books, New York, 1982. I read this in late-1996 - long after I had bought the book, which in turn was long after I first saw it - within a context of a frenetic personal inner quest, and at a specific circumstantial juncture of explosive psycho-emotional moorings. How can I describe what this book /tale means to me?!

The story is about a prince of Varanasi, who along with his friend learned the practice of mind-transference and was later tricked by the friend into being trapped in the body of a cuckoo. The friend enters the prince's body and usurps his place. The cuckoo-prince accepts his new situation as an opportunity to benefit others, and finding himself able to communicate not only with human beings but also with the birds and animals he lived among, he remains in the forest to teach them the Buddha's Dharma.

This is a mind-expanding story, a resource for personal transformation, nutrition tenderly provided to the starving soul.

Freedom Worldwide

In commemoration of the Schiller bicentennial in Mannheim in June 2005, an exhibition by Tatjana Mischke and Lukas Matthaei presented people engaged in different initiatives for freedom in places around the world.

The life and work of the people was shown in photos, since images can be understood worldwide without words. Images were provided as answers to 15 questions.

I had been invited to be a participant in the exhibition. The exhibit is accessible here.

Photo: Achinto