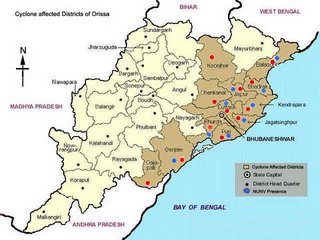

Orissa, a state along India’s eastern seaboard, adjoining the Bay of Bengal, was hit by an extreme cyclonic storm, in late-October 1999. Coastal Orissa was devastated by the combined action of storm surge, high speed cyclonic winds and local flooding.

An estimated 15 million people were directly affected. About 15,000 people perished. Over 10 million people were rendered homeless, over half a million cattle were lost, and most of the standing crops were destroyed.

Orissa is one of India’s poorest states. The levels of living and power of vulnerable populations in coastal Orissa are low, even though this is a relatively prosperous area of the state.

3 weeks after the super-cyclone, I visited the affected area as a member of the TARU team undertaking a rapid assessment of damage to housing and lifeline infrastructure. I reproduce below my field notes from our visit to Sahadabedi village, in Erasama Block of Jagatsinghpur District, Orissa.

One of the first things that strikes the visitor to this village - which is at least 10 kms inland - is the many shaven heads of small boys and young men. Many in this village, which lies within the worst affected belt, had perished.

The hamlet of Sahadabedi (under Jirailo village panchayat) had a pre-cyclone population of about 350, or 46 households. The adjacent Bengali Para hamlet consisted on 24 households. All the familes lived in mud (cob) houses with thatch roofs. The Bengali households (from Mednipur district in West Bengal) do not own any agricultural land, and they derived their livelihood from agricultural labour. Relations between the people of Sahadabedi and Bengali Para are said to be harmonious, with inter-community marriages also taking place.

78 people from this village were killed in the cyclone, 42 adult males, 22 children, and 14 women. 24 families in all lost their members. One entire family was killed, save a young son who was away attending a tailoring course. In another family, all were killed except an old woman and two young children.

This is a single paddy crop village, with a subsequent minor mung dal (lentil) crop. Because of inflow of sea-water into the Tibriya river adjacent to the village, farmers are unable to plant another crop. The village is flanked on the other side by the Hansua river. About 150 acres of agricultural land in all is owned by the villagers.

The villagers had been fore-warned about the cyclone, as early as on Tuesday 26 October 1999. But people thought there would only be strong winds and heavy rain, and that they would have to remain indoors. Rain and wind started on Thursday 28 October 1999. On Friday morning, at 4 am, very strong winds, from the N-NE direction started blowing. At 11 am, the surge of sea-water from the east hit the village: a huge wave of water, advancing with a roaring sound and topped by a smoke-like cloud of spray. Those who saw this were left speechless and paralysed in terror. The roofs collapsed over the houses and the water broke down the earth walls and destroyed the houses. People clutched at the roof and tree-tops in a bid to survive. Many were washed away. Tree braches broke in the fierce wind and those clutching these were carried away. Livestock were swept away.

People stayed in their perches on roof-tops, in the rain and wind, for 5 days, without any food or water. On the sixth day the government relief team arrived and provided relief supplies and materials. Many people sought shelter in a brick-RCC building in the adjacent hamlet of Ekghoria. They remained clutching one another in waist-deep water for 3 days, without any food or water, praying for succour.

Those with large houses, with a large, high roof, were able to save themselves by holding on to the roof. The only public building in the village, the Harwali Thakurani temple, also a mud-thatch structure, was also washed away. Only the image of the goddess remained.

About 450 heads of livestock were lost in Sahadabedi. Only 11 animals are left. All household assets, belongings, foodgrain and seed stocks, agricultural implements etc were lost. Because of inundation by sea water, the standing paddy crop has been entirely destroyed. Land productivity is expected to be significantly affected. People hope the next June crop will be realised, but expect a much lower yield. Restoring agricultural operations without livestock or implements or seeds has cast a pall of anxiety over the minds of farmers.

Riverbank embankments have been partially breached. Village paths have been buried under earth, debris and felled trees. A hand-pump served as the source of drinking water in Sahadabedi. This is being used again now.

The main road approach to the hamlet had been damaged and the approach paths to the hamlet were under water for several days after the cyclone.

Villagers together with outside rescue and relief workers and volunteers cleared and cremated the dead bodies. The villagers are in a kind of daze, numbed and in a state of shock, yet to fully digest that they have survived when so many, including close kin of many, had perished. They are just living on the little relief they have obtained and are beginning to realise the gravity of their plight and all that confronts them. “Our brain is not functioning”, they say. Their situation is dire, and they are unable to think out what they should do. Their immediate priority is to rebuild their house somehow. Restoring agriculture and ensuring next year’s crop is their next concern.

The revenue inspector was here 8-10 days ago to enquire about deaths and to list the damage to houses and loss of livestock. No intimation has been given yet on any financial assistance.

Making some arrangement to prevent the saline water inflow into the adjacent river Tigiriya is an issue the farmers are very concerned about. However, there has been no formal initiative on this from the government or panchayat side. Some 15-20 villages could benefit from such a scheme, through improved agriculture.

Having learnt from this cyclone, the next time there is a cyclone warning, people will take the matter more seriously. If arrangements are made to evacuate them, the villagers will readily leave. They realise the importance of building a cyclone shelter and say they are willing to contribute their voluntary labour to build a shelter at a suitable site that could cater to a number of villages and hamlets. This place can also serve as a school or a community hall, or a kirtan-bhajan (devotional singing) hall at other times.

There are no social or voluntary organisations working in this village. The people hope some food-for-work programme will be started. Because of loss of livestock, they are now thinking of using power-tillers and want assistance in this regard. They also want assistance for seeds and fertilisers.

Having seen and interacted with villagers across virtually the entire region affected by the cyclone, surge and related flood, there is clearly a tangible, qualitative difference, in the attitude and thinking of people in the isolated small villages in the worst-hit areas, who have personally experienced the death of many and been lucky to survive – in comparison to people in villages less affected. Though wanting assistance to rebuild their lives, they have a largely self-reliant demeanour. The people of Sahadabedi possess this spirit.

1 comment:

It is refreshing to know that the people of Sahadabedi possess such a strong spirit. You tell this story well. Excellent writing.

Post a Comment