A brief extract from Udayan Ghosh’s Khalasitolar Ami Ek Prodigal Khalasi (“I’m Khalasitola’s Prodigal Coolie”), translated by me.

(Udayan Ghosh) – Kamal-da, I ask you so many questions, I

hope you don’t get annoyed.

(Kamalkumar Majumdar) – I’m a student, can a student afford

to be annoyed while answering questions?

– May I ask you another question?

– Speak, my Lord.

– What’s the difference between painting and cinema?

– Ask Dhaenga this question. [dhaenga: colloquial / slang

for an abnormally tall, lanky person.]

– Dhaenga?

– Don’t you know Dhaenga? Your Horbola group’s Manik-babu. A

famous commercial artist.

– Oh, you mean Satyajit Ray? I don’t see him nowadays.

Horbola itself is now defunct.

– He used to come to Khalasitola earlier. On the pretext

of looking for Kamal-babu. Of course, he’d down a few glasses first, and then

enquire about Kamal-babu. Yes, he writes fine stories, nice, sweet,

incomparable stories. His drawing is not bad either, but everything’s

commercial. At least his father, Sukumar Ray, had a far superior film sense.

“’Twas a hanky, became a cat”. [ref. to Sukumar Ray's novella, Hajoborola, a classic of children’s literature in Bengali.] That’s cinema, a

montage in a movie. I heard that this Dhaenga is running after the other

Dhaenga, the political Dhaenga, Bidhan Roy, to make some song or gong … [ref.

to the novel Pather Panchali

(“song of the road”) by Bibhuti Bhushan Bandopadhyay, subsequently made into a

film by Satyajit Ray, that launched his career as a major film director of

Bengal, India and the world.] He’s also going to catch the poetic author of

(the novel) Aranyak, Bibhuti

Bhushan. Is it so simple? Has he ever written a poem in his life? Let him try!

Cinema is another kind of medium altogether, the greatest medium.

Shabda–brahma, rupa–brahma, and above all, a-rupa–brahma operate here.

Literature used to be translated into cinema only so long as cinema was in its

infancy. But now it is grown-up. So why would cinema accept literature as an element?

Haven’t you seen Eisenstein? Haven’t you seen Charles Chaplin? Yes, Dhaenga

knows music, but with just that, with story and music, you can’t cook up a

film. Image is imbued with life, and cinema is simultaneously imbued with life

and sound. Dhaenga is also a cine-club addict. When, from where, from which

film he’s copied or imbibed – can anyone here know that? What can one say …

Dhaenga does not know painting, the soul of a painting, and the colours fused

within that, he doesn’t even understand the power of the sketch lines let alone

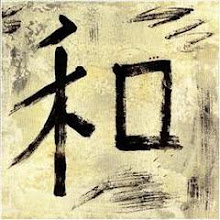

its sound-imbued version in cinema. Look at his cover of Banalata Sen, think about it. [ref. to the Bengali poem “Banalata

Sen” by Jibanananda Das, written in 1934, and Satyajit Ray’s cover for Das’s

collection of poems titled Banalata Sen (1942)]. Is “Banalata Sen” only about “her hair, like dark night in

ancient Vidhisha”? Or bird’s-nest-like eyes”? Is the meaning of the lines only

about her hair? In that case, what about all those lines – “evening arrives like the hush of dew

/ A hawk wipes the

scent of sunlight from its wings / All birds come home / all rivers / all of

this life’s tasks finished / … a manuscript begins preparations, then the

glimmer of fireflies illumines the delay of the story …” – is the meaning of all

this only “her hair … in ancient …”? Is the hair alone a metaphor for

all these sentences? And is Banalata Sen only a female face adorned by tresses? If

so, then what are “manuscript” and “story”? Let it be! “The delay of the story”, or “all of this life’s tasks finished” –

translating this visually is not the business of commerce, but of art. Why

then, dear dad, do you try your hand in the art of montage?

Reader, this is Kamal speaking,

it’s not as if I could render it exactly, my own writing is part of it.

Readers, forgive me. … But know this much, that these words are produced by

Kamalkumar.

Image: Cover of Jibanananda Das' Banalata Sen, designed by Satyajit Ray.